Reviews in Digital Humanities

A CELJ Conversation with Jennifer Guiliano and Roopika Risam, Reviews in DH editors

Debra Rae Cohen: Because this journal is so different from many of the ones that belong to CELJ , it would be great if you could start us off by explaining to us why you thought this journal was necessary, and what kind of gap it fills.

Jennifer Guiliano: Sure. So the journal started out as a bit of a lark, a bit of an experiment. Roopsi and I had been friends and had worked together on conferences and some other things and I was talking to her about my frustrations with how reviewing was operating within the field—for the purposes of conferences but also, more broadly, that there wasn't a lot of space in journals, either print journals or online journals, to cover reviews of digital projects. And it felt like a lot of times, when reviews were coming out, they were almost about what reviewers wished projects were, versus reviewing the project as it actually was. So I said to her, Roopsi, I wonder if there's a way to do this that is more efficient and speedy, but also addresses the broad diversity of the field? Not to speak for her, but I think that intrigued her a little bit. Like, what if we tried to play with something a little bit outside of the norm in the digital humanities?

Jennifer Guiliano, editor of Reviews in DH

Roopika Risam: At one point I was on the founding editorial board of DH Commons, which was a journal that tried to do this in the past. The journal had specified wanting mid-stage projects, but nobody knew how to define what a mid-stage project was. And the journal had also decided on a model where they had two different reviewers, a technical reviewer and a content reviewer. And that often became a challenge, particularly in mediating across these two very different ways of looking at projects. We were really invested in building up the capacity of the various communities within digital humanities to do peer review, but also our colleagues outside of digital humanities. So that led us to think about a model with one reviewer. Depending on the technical nature of the project, it may be a reviewer that's more situated in digital humanities, but it may be one that's more situated in a content area. We do a lot of mentoring and work to try and help each of those reviewers see how to evaluate the part of the project, whether it’s the content or the technical aspects, that may not necessarily be in their wheelhouse. It’s a collaborative enterprise not only to provide this outlet for reviewing, but also to really build capacity for reviewing of the projects, both in digital humanities and beyond.

Roopika Risam, editor of Reviews in DH

DRC: And if I'm not mistaken, you don't have anonymous peer review. Can you talk about that?

RR: In a sense, the anonymity of doing a review of digital humanities work is a folly because everyone's name is on their project, so we decided to just dispense with that. Instead, the name of the reviewer is not known to the project director until the review is published. But when it's published, the names of the project director or directors plus the reviewer are published together. So both the overview and the review have bylines, and the reviewers essentially get a publication. It's a model more akin to a book review. We were really inspired by the Bryn Mawr Classical Review book review journal, because we felt like that model made a lot more sense for an object like a digital humanities project.

JG: I think part of this is that we view review more as a conversation between the project and the reviewer than a critical takedown piece. Part of what goes into the open process is that we want everybody to feel like it is about being supportive of one another, both on the review side and on the product side. When we talk about what we're doing, it's about creating and supporting community. It’s not about, are you in or are you out? It's more about, can you tell everyone what you think matters? And are you following through on those statements in your humanities questions, your technology, your values—whatever it is that's motivating that project team? Where the reviewer really comes in is to say, you're doing a great job following through on the values you have or on the goals you have. Here's some other areas you might think about, or here's some ways to improve what you're already doing. And I think the open review process is about accountability to the project and accountability to the community.

Roopsi and I have been involved in all different kinds of reviewing activities, double-blind and single-blind and open, and we really, truly, feel like in the digital humanities space, it's just such a small community even though it's global. As she said, you can't not know who these people are. But, also, we want the reviewers to be able to feel like they've contributed to a project in a way that's meaningful. That’s part of our mentorship model: we ask all different kinds of people to review—cultural heritage specialists, students, graduate students, librarians, archivists, artists, technologists, all different kinds of people—because they are the people using these projects and using these tools. For us, the open process is really a commitment to accountability in a way that might not necessarily be there if we were doing this as a double-blind process or even a single-blind process.

RR: And just to add one more thing, if I may. The dialogic aspect happens in two ways. Sometimes a project director wants to reply or respond to a review. In that case, we invite them to write a response. Or sometimes they might fix a couple of things in response to the review, and they want to say, thank you so much for that feedback, we've changed these things. And we actually put that on the review page, which is the nice thing about being an open access journal. It creates connections that go on to exist beyond us and beyond the journal, so people get to know each other and follow up on conversations later.

DRC: At the same time, clearly the existence of this apparatus and this journal is also an intervention into the notorious difficulty that institutions have in evaluating, and even in talking about or understanding how to evaluate digital projects. Was that on your mind as well?

JG: I mean, yeah, for sure. Roopsi and I have done a number of reviews for promotion and tenure, or consultations with departments or programs about their process of evaluating and rewarding work. And both of us were involved in the Association for Computing in the Humanities when they developed their digital humanities guidelines for reviewing work. We’ve started with the notion that digital humanists have to do twice the amount of work, because they do their project, as it is, and then they have to spend a whole lot of time translating it into a traditional product as well, so that somebody who is not a digital humanist can understand it. We felt like that was an unfair burden, particularly for scholars of color, particularly for women, particularly for underrepresented communities in the field—asking them to do twice the amount of work without support is a barrier that is just incomprehensible.

And so, for us, giving the journal this space to do reviews was a way to push back against that pattern and to say, it's not so much about did they turn this into a book or did they turn this into an article. Instead, it’s: can they explicitly say what their intervention is into the humanities or what their intervention is into the technology? And can that be evaluated and seen? That was a really important intervention for us, because both of us had had experience where we had done digital work and gotten the reaction of, well, where's your book? Or where's the article that explains this to your discipline? For us, this was a space to say: no, this this work matters and should be seen for what it is, and not forced into a box that is hyper-disciplinary or hyper-specialized.

RR: And I would add that one of the challenges is that a lot of different professional organizations have developed guidelines, but if nobody knows to use them, what good are they? We didn't want to invent some new way of evaluating projects. We actually say, go to the disciplinary guidelines and take them into account as a reviewer when you're reviewing a project. We’re trying to encourage people to get familiar with and to use these guidelines that already exist.

One of the nice things that we've seen is that other projects have adopted our review process. One example is the Recovery Hub for American Women Writers: they do some reviewing of projects related to American women and literature and they use our process, and then they collect all of their reviews and we publish them as an issue. So we give a little more shine to their project and to the projects that they're featuring. That’s been a really wonderful partnership. And we have also had success in getting projects peer reviewed for people going up for tenure and promotion, that they can then put into their portfolios, so they've had a chance to have their work shine in that way too.

DRC: I wonder if you could turn now to some of the specifics about the ways that you've managed to implement all this. I know you have had special issues, and I'm wondering if that's if that's become part of the way that you use your topic editors, that they take responsibility for particular issues. Can you talk about how those come together?

JG: We have three different tracks in the journal. Roopsi can talk about open submissions. She manages that track. Special Issues started with us having conversations about areas of the discipline that we wanted to highlight, that we knew had really great work. We’ve had issues on Borderlands and Latinx and Jewish DH and Reviews in the Classroom and Sound and Pedagogy and Black DH—just topics where we were seeing great things at conferences and wanted everybody else to see the things they were doing. We started out by reaching out to people and saying, would you come on as a special issue editor, and we will help facilitate: we'll do all the emailing, we'll do everything, you just do some editorial work and help guide and that's it. The issue with those, we realized, is that we had so many one-off editors, and many special issue editors running at the same time because it's so based on when projects are available and when reviewers are available. And so, Roopsi and I were talking about capacity and where the fabric had sort of frayed in the process. And that's when we came up with the idea of topic editors.

RR: The topic editors—and editorial teams, because we encourage collaboration in the particular areas of interest that we've committed to—are ten editors in areas like African Diaspora and Asian Studies and so forth. They are responsible for around two issues a year and their role is to curate projects for an issue. Often they pick a theme for an issue—so, for example, we just had a Latinx Oral Histories special topical issue come out from the Latinx editors. They come up with reviewer ideas and write an editorial note, and our team handles all the solicitation emails and things like that. The idea there is for them to have a long-term relationship to the journal; it's a three-year commitment. We also encourage collaboration because these fields cross over each other—we have Social Justice and Pedagogy editors working on the Reviews in the Classroom special issue where you do a class, and we have a crossover between Social Justice and Queer Studies as well which has been very exciting. That's been a really wonderful way to move away from one-off editors.

Now the special issues can truly be one-offs, but can also be strategic ways for us to think about how we build long-term relationships for sustainability. For example, what does it mean to partner with a conference? And is there a potential way that an organization might actually kick in a little money towards the longer-term running of the journal in exchange for doing a conference special issue? So we try to be more strategic. But people still propose special issues to us on new topics. There is one on the Spanish civil war that I was actually looking at emails about this morning.

Anyone can submit a project for review to our open submissions process. We get a steady trickle of people saying please review my project, and sometimes if they fit a topic area, we might say, to a topic issue editor, is this something that interests us? We received a project related to Ukrainian digital humanities, and we're already having a special issue on endangered cultural heritage, so I said, we can do this! We keep things fairly in their buckets, but then there are these moments of synergy where we try to bring people and projects in line with each other.

Eugenia Zuroski: Can you recommend any particular things that people should look at if they want to get a sense of your journal? If people stumble across your journal for the very first time, what would you hope they would encounter to give them the best sense of what you are and what you do?

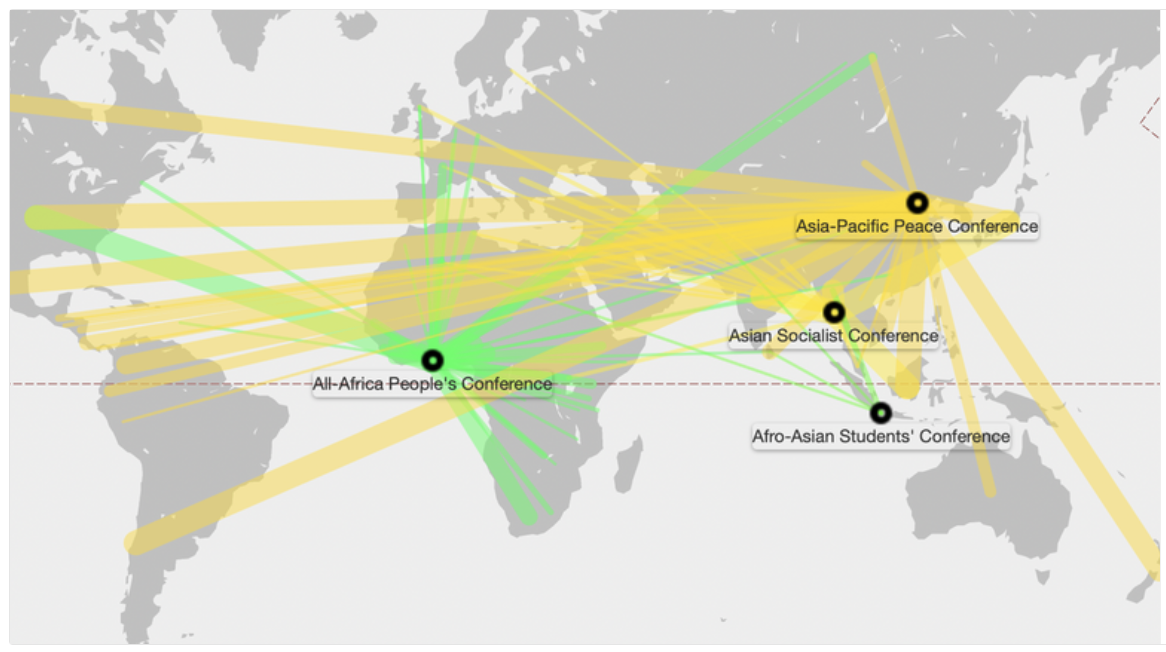

JG: Back in the day, when we started this, we actually created a project registry. So you could actually surf our journal based on topics and themes and methods and time periods. Our colleague Roxanne Shirazi has been working with us on updating that. It's actually a great way for newbies to come to our journal because they can pick what they like and what they're interested in. You can browse and surf the issues; we have some really great special issues that have come out, and they're all labeled. We just had one come out this month on Indian Ocean digital humanities, which is absolutely fabulous and a great starting point for someone (see Gallery below for thumbnails of reviews in that issue). But we're really all about discoverability; every publication comes out with a DOI, they're all in the registry, you can search and find them. Surf around and see what strikes your interests.

RR: I would say that our project registry has become the de facto way of finding digital humanities projects; this is actually why Mellon was interested in the work we were doing, because we had become this de facto discovery mechanism. And we find our journal on LibGuides not only because it's peer review of digital humanities projects, but it's also a great way to find projects. People use it a lot in their teaching so they can tell students, go and look, there's 200 projects to just browse through.

EZ: This is all this is so wonderful. And I want to note that everything that everything you're talking about, these are the conversations that we've been having among the Board at CELJ—these questions of how we shift our understanding of academic journals from the gatekeeping model to the mentorship and community-building model. But also, how can we as an organization, representing journal editors across disciplines and fields, do some of the support work of showing that journals are really the site where the standards and practices that define an active field and discipline get reproduced and reworked. Right now, with all of the interdisciplinary work and emergent disciplines like the ones that you're working with, there's so much work that needs to be done on establishing standards, on figuring out how flexible those standards are, and figuring out who's accountable to whom. So I just love hearing about this work happening.

But I want to ask a question that comes out of this, which is a question about labor. There is the specific labor that the two of you are doing as editors, including the labor of starting a journal up and getting it running, but how else is the labor organized or distributed that makes your journal possible, and allows it to do all the things that it's doing? And then attached to the question of labor is the question of other resources and support. Do you have funding that you have gathered from somewhere, especially because you're an open access journal? These are questions that a lot of journals are thinking about as they're considering moving online, moving to more open publishing models, that kind of thing.

RR: So Jen and I were talking about the journal in 2019 and spent that year working towards getting our first issue ready for publication in January of 2020. Originally, it was just the two of us, and we were just doing it as service, because that’s the expectation in the field. And we were very fortunate that Patricia Hswe of the Mellon Foundation had expressed interest in some support for Reviews in Digital Humanities. Typically, Mellon doesn't fund journals, but they were really interested in the model we were developing and the potential applications for that model. So they gave us $66,000 around mid-2020, which gave Jen and me small stipends but really paid for us to work with Educopia, which is a consulting firm. Educopia worked with us on thinking about long-term visioning for the journal, long-term sustainability, and governance and masthead structures. They had wide knowledge and ability to go out and see what other people were doing and bring that back to us and talk through that with us.

We developed an idea for managing phase two of the journal, trying to expand our outreach and expand the community, and that model was to bring on topic editors in the core areas that were really important to us and aligned with our values—African Diaspora Studies, Asian Studies, Indigenous Studies, community-engaged digital humanities, social justice pedagogy, and things like that. We’re very excited about this. Not that we necessarily want a structure where we have ten more editors to manage for perpetuity, but in the short term, this would be building communities within digital humanities in these topics.

And then there is the secession planning. Everyone always laughs at us when we say that we've been planning to not do this forever, just to continue to be the Jen and Roopsi show. We want this to really belong to the community and to have other people take ownership of it. As we were planning that, I made a move to Dartmouth, which came with access to resources that we did not have before, so we were able to bring on two managing editors to join the production editor who we had been able to hire with the first Mellon grant. So now we have Tieanna Graphenreed and Stacy Reardon joining Miranda Hughes, our production editor. That has helped tremendously, and we're able to pay them, which is wonderful. Stacey is a librarian, so she knows all the things. Tieanna is a graduate student whose work crosses over with digital humanities and just a great systems thinker, and really engaged in what's going on in the field. Them coming on freed us up to do a little bit of work on the big picture, long-term planning.

When the first Mellon grant ran out we asked Mellon for more money to actually implement the topic editor structure, and to pay the topic editors, to pay for translation, and also to buy Jen and me out of a little bit of our teaching so that we could still have more time to plan and also to work with the Nonprofit Finance Fund. We’ve hired them as consultants to help us with a budget model and in understanding the levers we can pull and push over time to find financial resources for the journal and that we can pass on to somebody else. So we're in the process of trying to set that up.

JG: You know, what was weird was that we started this as an experiment, as a pilot, we'd only initially planned on, like, a year to see whether it would hit or not—and it was like lightning striking. Within the first three months, it was clear that the community that we thought was going to be maybe bubbling a little bit was actually like a volcano. We went from having three or four projects that we were thinking about reviewing to having lists and lists of projects and people volunteering all over the place to review and submitting their projects and all of that. And so I think that for us, the labor question quickly became a question of capacity, and making sure that our labor met the capacity in a way that was sustainable and doable. And Mellon was pivotal on that.

But, also, it’s finding the right people. Miranda and Stacy and Tie are just incredible at what they do and are so good at helping Roopsi and me stay true to the vision of the journal and stay true to our values. When we think about the labor of the academy, one of the hardest things is that a lot of what we do is uncompensated, and so to have continuous funding for a set of years that allows us to bring on people who are also in the field has really been transformative for us. As Roopsi said, we do have an exit strategy. We do have an exit plan. Because we've seen journals where the labor is so immense that it becomes tied to a single faculty member and their position in the field—and neither of us knows everything about the field. Neither one of us is in a position to do this full time. So our goal is to be able to gift someone, at some point, a model that works and is sustainable, that they could then give to someone else at a later point.

I think that's our hope for the long term—to recognize everyone’s labor on an equal level, but also to be able to give something to someone that doesn't require having a really well-known institution with tons of money or doesn't require you to drop everything for four years, which is what a lot of journal editorships are like. What we really wanted was to make people aware of the holistic quality of the labor, from the project itself, through the review, through production, through the emails, through everything. When I think about what we're doing, if people never refer to the journal as Roopsi and Jen's project and just refer to it as Reviews in DH, then we've been successful. I think that's where it matters to us: having people shout out the journal for supporting their work. That's an incredible feeling every day.